Housing, Inequality and Abundance

#144 - I Lost a Dinner Bet—and Learned Why the American Dream Got Stuck

Hello friends, I hope you had a great week!

A few weeks ago, I had dinner with some friends from work in Luxembourg, and being a table with a bunch of finance colleagues we ended up talking about… money! Specifically the discussion was about global economy, income inequality, and the conversation quickly went to “how bad is it?”

I feel like Income Inequality is one of the biggest problems in our society, and same did my friend, but the discussion was “is now really worse than in the past”? My personal view was that things are actually bad but still a lot better now than in the past (where I pictured a stale “aristocracy-driven” society), while my friend was in the opposite camp (as several people at the dinner table, to be fair).

This discussion quickly went to a bet, to settle which we decided to confine the question a bit: if we take the U.S. as a reference point and use a specific metric to keep the debate grounded—how likely it is for someone born outside the top 5% of income or wealth to make it into the top 5% as an adult, and how did this evolve from 1980s to today.

I bet that for people born in the last decade mobility was a lot better than people born in the 1940s and I offered to buy dinner for everyone if I was wrong. Then I started researching it—and… I am afraid next time I travel to Luxembourg I will have to pay a dinner.

While I was trying to tweak the data to make my bet look more dubious and ultimately talk my way out of paying dinner, I actually stumbled on some content that I thought was relevant in this discussion and that added an interesting perspective.

One was a book, Abundance, which argues that housing scarcity is quietly throttling opportunity in America’s most productive cities. The other was a podcast interview with Adam Neumann (the WeWork founder), who’s now building a rental-housing startup that treats community as the core product.

I decided to write this post to give Raheel a victory lap, but also to share some reflections on the topic that I hope others will find interesting.

Mobility’s 50-Year Slide

The morning after that dinner bet I opened ChatGPT’s Deep Search and asked it to run a comprehensive analysis on my question: is mobility easier or harder today vs 40 years ago?

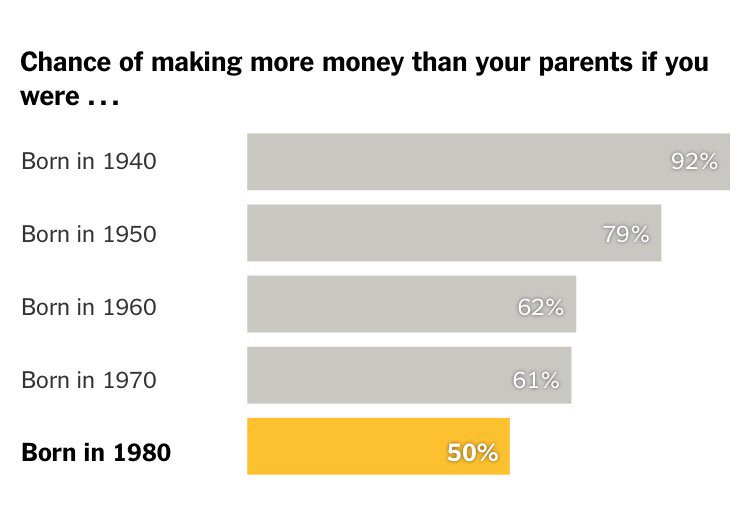

When we think about the American Dream, we often mean something basic: the idea that children will earn more than their parents. For much of the 20th century, that was exactly what happened. In 1940, 92% of U.S. children grew up to outearn their parents. But for kids born in the 1980s, the number drops to just 50%. And in high-opportunity places like Michigan and Illinois, upward mobility has fallen by more than half since the mid-century peak.

Relative mobility tells a similar story. A child born in the bottom fifth of the income ladder in the late 1960s had an 11% chance of reaching the top fifth as an adult. Fast forward twenty years, and that chance drops to 7.5%. Zoom in further to the top 5%, and the odds fall into the low single digits—roughly 3% or less for today’s cohort, according to estimates from Chetty’s tax data and PSID panel studies.

Worse, the distance between rungs has grown. Since 1977, the share of national income flowing to the top 1% has more than doubled, from 9% to nearly 19%. We’re basically back to where we were at the beginning of the 20th century.

When more of the economic pie goes to the top, it takes more effort (and luck) to move up even a few steps.

Europe mirrors this trend, with softer edges. Nordic countries still post higher relative mobility—14–16% of bottom-quintile kids reach the top—but that figure has stalled over the last two decades. In Italy, intergenerational mobility varies wildly: 22% in Milan, 6% in Palermo. Across the OECD, inequality is up and mobility is mostly sideways.

No matter which angle you choose—income, geography, or generational rank—the escalator still exists. But fewer people are allowed on, and it moves slower than before.

One final view: geography. Chetty’s Opportunity Atlas shows that where you grow up still plays an outsized role in where you end up. In cities with dense opportunity—like Salt Lake City or parts of the Midwest—upward mobility is stronger. In places with high segregation, low school quality, or unaffordable housing, it collapses. You can trace the odds of escaping poverty block by block.

Housing as the Bottleneck

As often happens to me when thinking about posts for this newsletter, I actually connected these insights with something non correlated. I am half way through the book Abundance by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson and when reading it there’s a sentence I highlighted in the part of the book where authors cover the role of housing and its importance for social mobility: “The new frontier isn’t the American West; it’s the hunt for an affordable lease in a city that still functions as an escalator.”

As shown by the data in the previous section, living in a city is a massive factor for social mobility.

The metaphor with the Far West stuck with me. For most of U.S. history, land on the horizon signaled fresh opportunity; the author argue that today that type of opportunity is often linked to the ability of moving to a city, getting a better education, a higher paid job, better opportunities and ultimately improving income as a result.

If that’s the case, being able to afford a house in a city becomes a key factor of social mobility. And the authors argue that house shortage is actually a key cause for the lower social mobility the US are seeing, especially in some areas of the Country.

Low housing supply means higher prices. In 1950, the average American needed 2.3 years of wages to buy a median home. By 1980 that was 3.8 years. In 2000, 7 years. Today, the national average is above 8, with coastal metros reaching 15 years of income. The price of entry into cities has outpaced the ability of many workers to follow opportunity.

Worse, the places with the most jobs tend to have the least buildable land. San Francisco prohibits multifamily housing on three-quarters of its residential land. Boston requires one parking space per unit, even downtown. Los Angeles has similar ratios. Each restriction limits supply, drives up prices, and freezes out people who don’t already own.

Meanwhile, cities that do allow building—like Tokyo, Houston, and parts of the U.S. Sun Belt—see lower rent inflation, higher in-migration, and better mid-skill wage growth. But those are the exceptions.

We can pour money into training, education, and innovation—but if people can’t afford to live near opportunity, those programs will under-deliver.

Housing isn’t a side issue. It’s the infrastructure that makes mobility possible.

Flow’s Bet on Community-as-a-Service

The second random connection I made to the social mobility topic was listening to this podcast episode of A16Z founders interviewing Adam Neumann, the founder of WeWork.

When I first read about a16z investing $350 million in Adam Neumann’s new startup, I rolled my eyes. Honestly, I thought: how the hell are they backing the guy behind the most spectacular implosion in Silicon Valley? It looked like a parody of venture capital excess—a redemption arc nobody asked for, propped up by a massive check.

But then I listened.

Neumann did a podcast where he laid out the thesis. And for all his theatrics, the idea wasn’t crazy. In fact, it made uncomfortable sense. And I found myself thinking less about Neumann, and more about a16z. It takes a rare kind of contrarian conviction to back the person everyone else wrote off—and to place a bet on housing, a sector most tech VCs avoid like the plague. The more I listened, the more I respected the move.

Because if you believe that renting has become the default setting for an entire generation (life renter writing, so recognize the bias!)—and that cities are the new frontier of mobility—then Flow (Adam Neumann’s new venture) isn’t a crazy idea. It’s a high-conviction wager on a structural shift.

So what is Flow, really?

At a basic level, it’s a property platform: by 2025 it manages around 6,500 units across cities like Miami, Nashville, Fort Lauderdale, and Riyadh. The company offers flexible leases (from one night to one year), digital services (door codes, maintenance, meetups), and a hospitality layer (on-site events, wellness perks, even a membership vibe).

Andreessen Horowitz saw two things. First, the scale: U.S. multifamily housing is a $3 trillion asset class, and renters now make up nearly 37% of households. Second, the demographic tailwind: as homeownership drifts out of reach, the idea of renting “forever” isn’t fringe anymore but it’s rather mainstream now.

Flow is surfing the wave of social mobility I was talking about at the beginning of the post! It makes sense!

Of course, Flow doesn’t solve housing scarcity. It still buys in expensive markets. It doesn’t bulldoze zoning laws or add missing supply. But that might not be the point.

What Flow does represent is a shift in expectations. If people are stuck renting for life, they’ll want more from the experience: community, stability, and yes, maybe even a stake. I still don’t know if Flow will succeed. But I no longer think it’s a joke. It’s a bet on the idea that how we live is changing—and someone will build the brand that defines that shift.

Madrid: proof that building pays

Abundance argues that when cities behave like the nineteenth-century frontier the mobility “escalator” restarts on its own. And the final dot on today’s post is a reflection I was sharing with my wife last week, as we spent the week in Madrid (where we have lived for a few years). We were staying in an area of town that when we moved there, only 5 years ago, was full of cranes and construction sites. And it is now a new vibrant neighborhood.

For anyone familiar with the Spanish economy, it’s quite evident that real estate plays a big role. And I argue that the continuous real estate expansion is a big factor to how the city’s cost of living is materially lower than other capitals in EU like London, Paris or Milan.

Madrid’s cost-of-living index sits around 58 on Numbeo, roughly 40 points below New York and well under most Western European capitals. A single person can still cover monthly basics (excluding rent) on ≈ €830, and the median apartment runs about €6,100 per m² city-wide—half London’s and a third of Paris’s headline numbers.

And I argue that, like I stated at the beginning of the post, affordability buys talent. Spain recorded 642,000 net migrants in 2023, and Comunidad de Madrid captured the biggest share—150,000 people, more than any other region. Many arrive with laptops: Sequoia counts 53,000 engineers in the metro, the third-largest pool in Europe, while local officials tally 2,100 active tech start-ups—momentum strong enough to push South Summit’s annual deal count to record highs. Remote-work rankings now pitch Spain as “the best place to be a digital nomad,” citing the visa regime and living costs.

Macro numbers hint at the flywheel. Spain is set to grow ≈ 2.5 % in 2025, topping the euro zone. There’s an argument that a city that keeps rents in check can still lure high-skill workers, who then lift aggregate output, validating Abundance’s thesis that concrete and cranes beat tax breaks and slogans.

Madrid isn’t perfect—rents jumped 50 % since 2020, and vacancy is shrinking—but compared with the supply-starved coasts of the U.S. it looks like a live demo of what happens when a big market keeps saying sí to building. If the frontier has moved from open plains to open zoning codes, Madrid offers a glimpse of how that frontier can still push mobility forward.

By contrast, Berlin—once celebrated as Europe’s “poor but sexy” frontier of creativity and affordability—has over the last decade flipped into a cautionary tale. From 2010 to 2015 alone, rents jumped ~32% and housing sale prices ~68%, siphoning an ever-larger share of income into rent (rising from 18% to 29% of average household income) . Berlin have climbed about 11% year-over-year as of mid‑2025. Despite intensified tenant protections, high demand and lack of new supply have left newcomers and lower-income residents scrambling for housing . In a city once prized for bohemian culture, rising costs are hollowing out its character—and limiting the very mobility it once enabled.

I lost the dinner bet, and this means I won’t be going to Luxembourg for the next few years so that I don’t have to settle (just joking, I will settle soon!) but I learnt a lot of interesting things and connected dots I had not linked before. The data showed that the post-war escalator stalled decades ago, and the deeper I looked the clearer the mechanism became. Whether you read Chetty’s tax tables, Abundance’s polemic, Flow’s pitch deck, or Madrid’s construction stats, they all circle the same point: social mobility travels on poured concrete and approved floorplans. When housing supply stays elastic, wages stretch further, talent migrates, and the odds of outrunning your parents tick up. When supply locks, even six-figure salaries scrape against rent.

For mid-century Americans, the frontier was a mortgage in the suburbs. For today’s grads, it might be a co-living lease in Miami, or a tech job in Chamartín at half the Paris cost. The ladder still exists, but leaving where it’s legal to build the rungs has become even more important.

I wish you an amazing weekend,

Giovanni